The Fate of No Sleep: Fatal Familial Insomnia

To virtually all species, sleep is integral for survival and good health. Unfortunately, sleep doesn't always come easily. With humans, for instance, the inability to attain a good night's rest might stem from various life stressors, health conditions or even too much caffeine. Regardless, performing day-to-day tasks after consecutive days without proper sleep is often debilitating. Fortunately, for most, a few days of improper sleep is likely impermanent and only a result of temporary circumstances. However, there are instances where the choice between sleep and no sleep is not a conscious decision. One such instance is insomnia, a sleep disorder that affects the lives of approximately 30% of the adult population.

10

In the case of insomnia, there are those who simply struggle to sleep, and others that may stay wide awake for days on end, falling into a descent of hallucinations rather than falling asleep. With the loss or absence of sleep, insomniacs find their own livelihood slowly wither away with the worsening of proper physical, social and mental functioning.

10

As such, insomnia is an incredibly dangerous disorder. While insomnia is a widely known disorder, there is an existing rare genetic variant of insomnia, known as Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI). There are only about 57 reported cases of FFI that exist in 27 familial lines.

9

In addition to its rarity, FFI is noteworthy as it is a disease that lands in the dangerous half of the insomnia spectrum, with most of its patients dying of the disease only a few years following initial diagnosis.

Genetics:

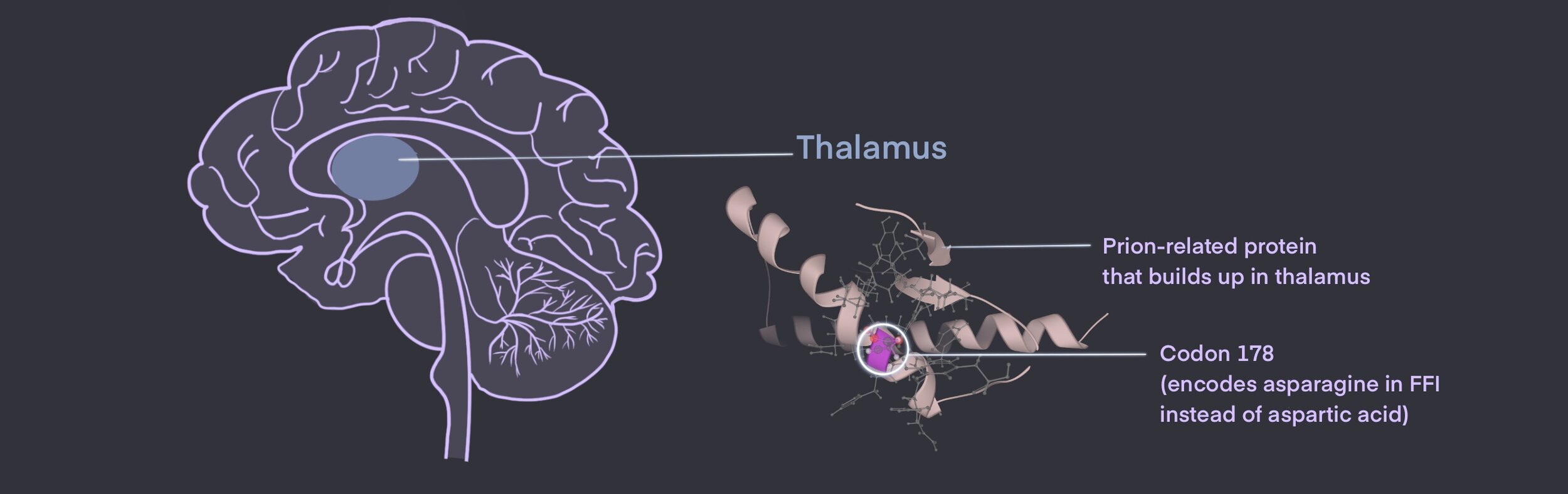

FFI is a prion disease, which is a branch of neurodegenerative disorders caused by misfolded prion proteins. 3 More specifically, FFI belongs within the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies category.3,9 The function of the prion protein, normal or misfolded, is currently unclear.3

However, the misfolding of proteins typically denotes the creation of an unwanted function and/or the loss of an important function. What makes the prion protein particularly perilous is its unfortunate property of often being misfolded into abnormal conformations and accumulating in the brain. Some more commonly heard examples of prion disease include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (also known as “mad cow disease”).1

FFI is often inherited through an autosomal dominant pattern, which means that one copy of the mutation passed on from parent to offspring is enough to cause the disease.7 This mutation occurs on codon 178 at the prion-related protein (PRNP) gene 7 Here, normal aspartic acid (Asp) is substituted for asparagine (Asn), causing abnormalities and the creation of a misfolded prion protein.7

As mentioned previously, the exact function of misfolded prion proteins remains unclear, but its impact is knowingly toxic to the body.3,9 In FFI, these prions build up mostly within the thalamus of the brain. 2,3,7

Due to the toxicity and accumulation of these prions, a progressive loss of thalamic neurons occurs. With the loss of thalamic neurons comes the degeneration of many thalamus-related functions, such as the relaying of motor and sensory signals, consciousness and alertness. The degenerative changes of this area of the brain can explain the variety of symptoms seen in FFI, especially disturbances in the sleep-wake cycle and insomnia.

Furthermore, there are cases where individuals that carry the PRNP gene mutation do not ultimately manifest this disease nor exhibit any symptoms.8 This indicates the incomplete penetrance of FFI, meaning that not all carriers of the mutated gene are affected. Interestingly, an even rarer version of this disease, called sporadic fatal insomnia, occurs randomly without a variant PRNP gene.

6

Symptomatic Progression:

As dawned by its own name, this disease is most characteristically identifiable by insomnia. This insomnia becomes progressively worse over time; lack of sleep leads to both physical and mental deterioration, comas and even death.3 FFI’s symptomatic progression typically follows 4 stages. 7

In the first stage, the disease is best identified by insomnia, which worsens over a period of a few months and results in psychiatric symptoms such as phobia, paranoia, and panic attacks.7 Some also report lucid dreaming during this period. 7

The onset of this first stage typically occurs in a patient’s midlife, around the ages of 36 to 62.9

Stage two encompasses the next five month period in which psychiatric symptoms heighten along with insomnia.7 Individuals with FFI may experience hallucinations, increased apathy and increased somnolence as a result of the deprivation of proper nocturnal sleep. 9

Another common symptom of FFI is autonomic dysfunction as hyperactivity in the sympathetic nervous system occurs.7

A variety of symptoms associated with autonomic dysfunction may come about as a result, such as fever, rapid heart rate (tachycardia), high blood pressure (hypertension), increased sweating (hyperhidrosis), increased production of tears, constipation and sexual dysfunction.7

Stage three occurs for approximately three months following stage two.7 In this stage, the individual with FFI often experiences complete insomnia and disruptions of the sleep-wake cycle. 7 As time goes on, these individuals may also experience episodes of dream enactment, in which they will display jerking movements (myoclonus) so as to mimic the content of dreams that they are able to recall upon “awakening”.9

The fourth and final stage of the disease can last for six months or more.7 This stage is characterized by rapid cognitive decline and progressive dementia (forgetfulness to hallucinations).7The individual with FFI may experience an inability to voluntarily move or speak, vision problems and swallowing problems, which can be followed by a coma and eventual death. 7 The four stages typically occur over an 18.4 month or 1.5 year period on average. 6

In such a period, the rapid worsening of physical health is overwhelming. Additionally, some serious psychiatric and mental health issues also come as a result of FFI—a consequence of both insomnia symptoms and environment. For instance, FFI patients are also commonly diagnosed with anxiety and depression, which may arise as a result of increased apathy over the image of FFI as a terminal disease. 7

Treatment:

Unfortunately, given the rarity of this disease, a viable cure or disease-modifying treatment has yet to be found. Most individuals suffering from FFI typically work alongside a team of neurologists, psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers in order to form a comprehensive treatment plan. 3

Additionally, there are treatments and drugs available to reduce the various symptoms of FFI, such as clonazepam for myoclonus, antiepileptic drugs and antidepressants.

3,5

It is also particularly important that patients abstain from using medications that may increase confusion or insomnia.

As there are so few cases of FFI, some difficulties arise when planning and performing treatment trials. While it would be undoubtedly beneficial for more numerous and larger treatment trials to take place, a great barrier is that many patients pass away over the course of the studies due to the rapid progression of FFI. As such, treatment trials are often limited to smaller groups of patients with the disease. These treatment trials often focus on the effects of three drugs: flupirtine, quinacrine and doxycycline.

4,5,11 While the observational studies on these three drugs had previously shown an increase in survival rate, new adequately controlled studies do not support the same result.

5,11 Therefore, the effect of both flupirtine, quinacrine and doxycycline are largely inconclusive. Another therapeutic application is also in the works, known as antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs). ASOs target and degrade PRPN RNA to reduce the amount of encoded toxic prions.

11

In particular, it may be important to increase research into raising awareness of FFI and educating health professionals. A shift in this direction can help health professionals identify and diagnose individuals with the disease earlier on. One suggested method for the early identification of the disease’s onset is prodromal biomarkers or biochemical tests that detect certain characteristic pathological changes in the brain and body.

11

Earlier diagnosis would allow for faster intervention, which could potentially increase survival rates.

Despite the difficulties and lack of funding put towards rare disease research, further research for FFI is significant in that it can help improve the lives of many individuals. Furthermore, FFI research may lead to tangential discoveries, such as a better understanding of all prion diseases.

Support Groups:

Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Foundation is a support group for those affected by prion diseases, such as FFI, and their families.

Tiffany Yu

References

- Burchell JT, Panegyres PK. Prion diseases: immunotargets and therapy. ImmunoTargets and Therapy. 2016;5:57-68. doi:10.2147/ITT.S64795

- Cracco L, Appleby BS, Gambetti P. Chapter 15 - Fatal familial insomnia and sporadic fatal insomnia. Pocchiari M, Manson J, eds. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 2018;153:271-299. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63945-5.00015-5

- Fatal Familial Insomnia. National Organization for Rare Disorders. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/fatal-familial-insomnia/. Published 2018.

- Forloni G, Tettamanti M, Lucca U, et al. Preventive study in subjects at risk of fatal familial insomnia: Innovative approach to rare diseases. Prion. 2015;9(2):75-79. doi:10.1080/19336896.2015.1027857

- Hermann P, Koch JC, Zerr I. Genetic prion disease: opportunities for early therapeutic intervention with rigorous pre-symptomatic trials. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2020;29(12):1313-1316. doi:10.1080/13543784.2020.1839048

- Imran M, Mahmood S. An overview of human prion diseases. Virology Journal. 2011;8(1):559. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-8-559

- Khan Z, Bollu PC. Fatal Familial Insomnia. StatPearls. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482208/. Published 2020.

- Medori R, Tritschler H-J, LeBlanc A, et al. Fatal Familial Insomnia, a Prion Disease with a Mutation at Codon 178 of the Prion Protein Gene. New England Journal of Medicine. 1992;326(7):444-449. doi:10.1056/NEJM199202133260704

- Montagna P. Fatal familial insomnia: a model disease in sleep physiopathology. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9(5):339-353. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2005.02.001

- Roth T. Insomnia: Definition, Prevalence, Etiology, and Consequences. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2007;3(5 Suppl):S7-S10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1978319/

- Vallabh SM, Minikel EV, Schreiber SL, Lander ES. Towards a treatment for genetic prion disease: trials and biomarkers. The Lancet Neurology. 2020;19(4):361-368. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30403-X

Cite This Article:

Yu T., Ahmed R. & Pham E. The Fate of No Sleep: Fatal Familial Insomnia. Illustrated by S. Chen. Rare Disease Review. October 2021.