Whipple’s Disease: A Series of Differential Diagnoses

Brief Summary of Disease

Whipple’s Disease is a systemic infectious disease caused by the bacterium Tropheryma whipplei.1 This bacterium was long considered rare; however, more recent data has confirmed that it is common in stool samples.2 Many individuals are asymptomatic carriers of Tropheryma whipplei. Despite the potential for Whipple's Disease to occur at any age, it is rarely found in children.3 The disease predominantly affects Caucasian males with a mean onset at the age of fifty.3 Though there are not many reported cases, the presentation of Whipple’s Disease mimics many other disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, neurological conditions and gastrointestinal conditions.4,5 Whipple’s Disease can be effectively treated and managed when it is recognized early enough.4 However, since it presents much like various other conditions, it could be misdiagnosed or be left untreated resulting in disease progression, permanent disability or even fatality.5

“Most individuals who are exposed to Tropheryma whipplei are asymptomatic carriers and produce a protective immune response which halts the spread of the bacteria or clears the body completely of it.”

Etiology and Pathology

The genetic predisposition of the individual who comes into contact with Tropheryma whipplei influences the susceptibility to and the severity of Whipple’s Disease.6 Most individuals who are exposed to Tropheryma whipplei are asymptomatic carriers and produce a protective immune response which halts the spread of the bacteria or clears the body completely of it.7 It has been proposed that two alleles HLA-DRB13 and HLA-DQB106, are present more frequently in those with Whipple’s Disease than in healthy individuals who have been exposed to the bacteria.8 In individuals with these alleles, the inflammatory response to the bacteria is muted. This leads to an impaired response by type 1 helper T-cell, a white blood cell that is responsible for helping macrophage activation and function. Macrophages are immune cells that are responsible for helping in the effective clearing of bacteria. Essentially in individuals with HLA-DRB13 and HLA-DQB106, the immune system cannot effectively attack and clear the Tropheryma whipplei bacteria. Those with Whipple’s Disease are at a life-long susceptibility for reinfections with new strains and relapses. 9

Symptoms

“For one-third of Whipple’s Disease patients, joint pain and other nonspecific symptoms will precede the classical gastrointestinal and systemic symptoms by several years.”

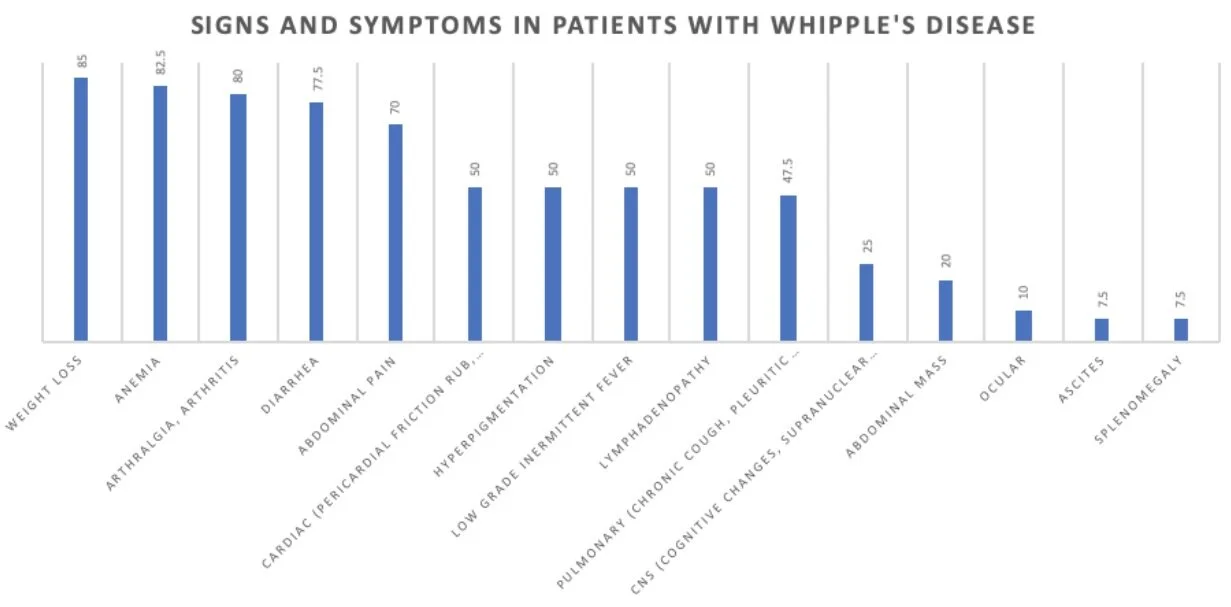

The most common symptoms of Whipple’s Disease are weight loss, diarrhea, joint pain and anemia (Figure 1). 3 For one-third of Whipple’s Disease patients, joint pain and other nonspecific symptoms will precede the classical gastrointestinal and systemic symptoms by several years. This makes diagnosing Whipple’s Disease rather difficult for practitioners, as these initial symptoms could indicate a wide variety of other conditions. Many cases of Whipple’s are initially misdiagnosed as rheumatoid arthritis due to the presentation of joint pain years before the onset of gastrointestinal symptoms. 3 Low-grade fever, night sweats and enlarged lymph nodes are common symptoms that could lead to a lymphoma differential diagnosis. Lymphomas can also cause similar gastrointestinal manifestations. 3 Intestinal symptoms in Whipple's Disease are nonspecific so clinicians often suspect other conditions such as Crohn's disease, celiac disease, and amyloidosis. 3 When gastrointestinal symptoms do manifest, the disease usually progresses rapidly. A large variety of symptoms ensue; diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, muscle wasting, weakness, anorexia, shortness of breath, cough, headache, low-grade fever, anemia and vitamin deficiencies. Extraintestinal symptoms can present as well, such as pulmonary hypertension, congestive heart failure, inflammation of the lining of one or more heart valves, inflammation of the serous membranes, metabolic bone disease, cognitive disorders and neurological signs. 10 Neurologic symptoms are in a category of their own as they may appear with or without gastrointestinal or joint symptoms. 3

Figure 1: Signs and symptoms in patients with Whipple’s Disease adapted from Dutly et al. 3

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of Whipple’s Disease is complicated, especially since many symptoms are similar to other more common conditions. The clinician will rule out other conditions before diagnosing a case with Whipple’s Disease. An endoscopy is the insertion of a flexible tube that reaches the small intestine with a camera attached to it.

12

This tool will help the clinician look for lesions of Whipple’s Disease. In particular, the clinician will look for a thick and creamy appearance in the intestinal wall as this is a potential indicator of Whipple’s Disease.

12

The removal of a small piece of intestinal wall tissue through a biopsy may be performed to test for the presence of Tropheryma whipplei bacteria.

12

Foamy macrophages, an abnormal type of immune cell, in the biopsy samples will confirm the presence of Tropheryma whipplei bacteria.

12

Receiving antibiotics before diagnostic testing can result in a false negative.

12

“90% of patients are responsive to antibiotic therapy; however, untreated Whipple’s Disease can be fatal. ”

Prognosis

The prognosis of Whipple’s Disease is poor when left untreated. Antibiotic therapy that penetrates the blood-brain barrier is necessary as Tropheryma Whipplei can be found in the patient’s cerebrospinal fluid. 90% of patients are responsive to antibiotic therapy; however, untreated Whipple’s Disease can be fatal. Difficulties occur for the clinicians when the results of the diagnostic investigation are contradictory or difficult to interpret. Such results may lead to an incorrect exclusion of the disease and possible death in a highly treatable disease.

11

Ceftriaxone or benzylpenicillin are two antibiotics that are commonly used to treat bacterial infections. Daily intravenous administration of one of the antibiotics is given every four hours for patients with Whipple’s Disease without central nervous system (CNS) involvement. If CNS is involved, the patient is given double the dose of benzylpenicillin. This is then followed by trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, an oral antibiotic, twice a day for one year.

13

There are alternatives for patients allergic to ceftriaxone or benzylpenicillin.

13

Since the bacterium can persist latently in the body years after treatment, there is a 9-15% recurrence risk once the treatment regimen ends.

14

CNS involved patients are at an increased risk of recurrence.

13

Relapse occurs within 4.2 years of initial diagnosis but some patients relapse after over 30 years.

14

Annual clinical checks are recommended as a follow up to treatment.

13

Current Research

Current research recommendations are that in cases of clinical suspicion of Whipple Disease, it is important to identify diagnostically the presence of Tropheryma whipplei.

15

The standard guideline for treating the condition is through antibiotic therapy lasting several months to years.

15

Despite antibiotic therapy being in practice since the 1950s, best antibiotic combination and duration of therapy has yet to be determined.

16

Although trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is currently used for long-term therapy of Whipple’s Disease, it may not be the best choice as it can cause hematological disturbances due to folic acid deficiency and Steven-Johnson syndrome.

16

French authors claim doxycycline to be a better option as it has great bioavailability and has been used long-term in treating malaria without pertinent adverse effects.

16

Controlled prospective trials are needed to determine the best therapy for Whipple’s Disease; however, current research indicates that the standard therapy of ceftriaxone and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole should be used for one year followed by lifelong doxycycline.

16

Recurrences of Whipple’s Disease are possible due to the various strains of the bacterium.

16

It is hard to distinguish a new infection with a different genotype from a relapse.

16

Clinical follow-ups tests are recommended for life.

16

Novel presentations of Whipple’s Disease have been reported in the last couple of years. For instance, even though we know that Whipple’s Disease may be accompanied by CNS complications, rarely do we see Whipple’s Disease solely with CNS confinement.

17

Recently, there was a case reported of Whipple’s Disease presenting exclusively as a cystic brain tumour where the individual in question was experiencing seizures.

17

The patient was treated with a standard course of antibiotics and recovered well.

17

Therefore despite novel presentations, the current treatment standard is still effective.

Anjali Sachdeva

Works Cited

- Marth T. Systematic review: whipple's disease (tropheryma whipplei infection) and its unmasking by tumour necrosis factor inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015; 41(8):709-724. doi:10.1111/apt.13140

- Raoult D, Fenollar F, Rolain JM, Minodier P, Bosdure E, Li W, et al. Tropheryma whipplei in children with gastroenteritis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16(5): 776-782. doi: 10.3201/eid1605.091801

- Dutly F, Altwegg M. Whipple’s disease and “tropheryma whipplei.” Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(3):561–83. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.3.561-583.2001Glaser C, Rieg S, Wiech T,

- Scholz C, Endres D, Stich O, et al. Whipple’s disease mimicking rheumatoid arthritis can cause misdiagnosis and treatment failure. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12: 99. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0630-4

- Weisfelt M, Oosterwerff E, Oosterwerff M, Verburgh C. Whipple’s disease presenting with neurological symptoms in an immunosuppressed patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2012.5882

- El-Abassi R, Soliman MY, Williams F, England JD. Whipple’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2017;377:197–206. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2017.01.048

- Dolmans RAV, Boel CHE, Lacle MM, Kusters JG. Clinical manifestations, treatment, and diagnosis of tropheryma whipplei infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30(2):529–55. doi:10.1128/CMR.00033-16

- Martinetti M, Biagi F, Badulli C, Feurle GE, Müller C, Moos V, et al. The HLA alleles DRB1_13 and DQB1_06 are associated to whipple’s disease. Gastroenterol. 2009;136(7):2289–94. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.051

- Fenollar F, Lagier J-C, Raoult D. Tropheryma whipplei and whipple’s disease. J Infect. 2014;69(2):103–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2014.05.008

- Bureš J, Kopáčová M, Douda T, Bártová J, Tomš J, Rejchrt S, et al. Whipple’s Disease: our own experience and review of the literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/478349

- Jessamy K, Appiah R, Anozie O, Ojevwe F, Ubagharaji E, Antoine S. Is it whipple disease or sarcoidosis? a diagnostic dilemma. CHEST. 2016;150(4):191A. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.200

- Crews NR, Cawcutt KA, Pritt R, Virk A. Diagnostic approach for classic compared with localized whipple disease. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018; 5(7):ofy36. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy136

- Melas N, Haji Younes A, Egerszegi P. Whipple's disease: rare, fatal without treatment, but easily cured. Lakartidningen. 2019; 116:1-5.

- Ruggiero E, Zurlo A, Giantin V, Galeazzi F, Mescoli C, Nante G, et al. Short article: relapsing whipple’s disease a case report and literature review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(3):267–70. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000539

- Sluszniak M, Tarner IH, Thiele A, Schmeiser T. The rich diversity of whipple’s disease. Z Rheumatol. 2019; 78(1):55-65. doi:10.1007/s00393-018-0573-8.

- Biagi F, Biagi GL, Corazza GR. What is the best therapy for whipple's disease? our point of view. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017; 52(4):465-466. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1264009.

- Kilani M, Njim L, Nsir AB, Hattab MN. Whipple disease presenting as cystic brain tumor: case report and review of the literature. Turk Neurosurg. 2018; 28(30):495-499. doi:10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.17111-16.2.

Cite This Article:

Sachdeva A., Huicochea-Munoz M., Kord D., Chan G. Whipple’s Disease: A Series of Differential Diagnoses. Illustrated by S. Montakhaby Nodeh. Rare Disease Review. November 2020.

DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.28426.49605