Progeria: Race Against Time

Born in 1996 and raised in the Patriots’ hometown near Boston, Sam Berns was an avid sports fan. He even joined his high school’s marching band, playing a specially designed snare drum.1 Sam’s dreams were unlike those of many children his age: “I will like to become an inventor when I grow up, kind of like Einstein and Steve Jobs combined.”2 Sam Berns was not ordinary. He was afflicted with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), or commonly known as progeria, which caused him to age prematurely. It led to growth failure, aged-looking skin, bone and joint problems, and heart complications that are reflective of old age. Despite knowing this, Sam continued to maintain a positive outlook on life, and died at the age of 17. Now, imagine your whole life span reduced to mere 14 years in all. How would you race against time in search for a cure?

““A very peculiar withered or old-mannish look, all his features being thin and pinched.””

Just like Sam, all of the children diagnosed with progeria never live to experience adulthood, as the average life expectancy of progeria is 14.5 years.3 The first ever reported case of progeria was by a physician named Jonathan Hutchinson in 1886 when he examined a three and half year-old boy exhibiting signs and symptoms characteristic of the disease. The boy was described to have a “very peculiar withered or old-mannish look, all his features being thin and pinched.”4 The boy’s head was large, his scalp thin, and he could not walk perfectly, always keeping his knees a little bent.4 Along with Hutchinson’s report, Dr. Hastings Gilford also accounted for a novel case of progeria in his book, Progeria, A Form of Senilism, in 1904, relating progeria to delayed development, combined with premature old age.5 Thus, the disease was named after these two physicians, as they both presented an excellent clinical picture of progeria as a syndrome resembling aging with onset in the first year after birth.3 Through Hutchinson’s and Gilford’s efforts, it was established that progeria was a rare and fatal genetic disorder. However, for over a century after this initial discovery, there was almost no progress in understanding the genetic origin of progeria. This complete lack of information regarding the disease meant that there was no known cause, no funding for progeria research, no treatments, and no organizations advocating for the children suffering from progeria, who were left in a world of uncertainty.

How do you cure something that has no known cause or diagnosis? How do you search for a cause when you have no support, whether financial or community wise? Sam Berns was just like any other case of progeria, but he became the face of a movement that aimed to race against time in search for a cure for the children who only have 14 years to live. Sam’s parents, two physicians named Leslie Gordon and Scott Berns, refused to accept that there was nothing they could do for their child. So in response to the extreme absence of information regarding progeria, the Progeria Research Foundation was created in 1999, just a year after Sam’s diagnosis.7 The lack of attention has since been transformed into worldwide recognition of progeria, a first-ever treatment that improves the conditions that are reflective of old age, and progeria seated at the forefront of scientific efforts to discover additional treatments and a cure.4 It took only about five years for the organization to discover the exact cause of progeria in 2003, whereas for over a century before this remarkable gene discovery, the world had been living in obscurity.

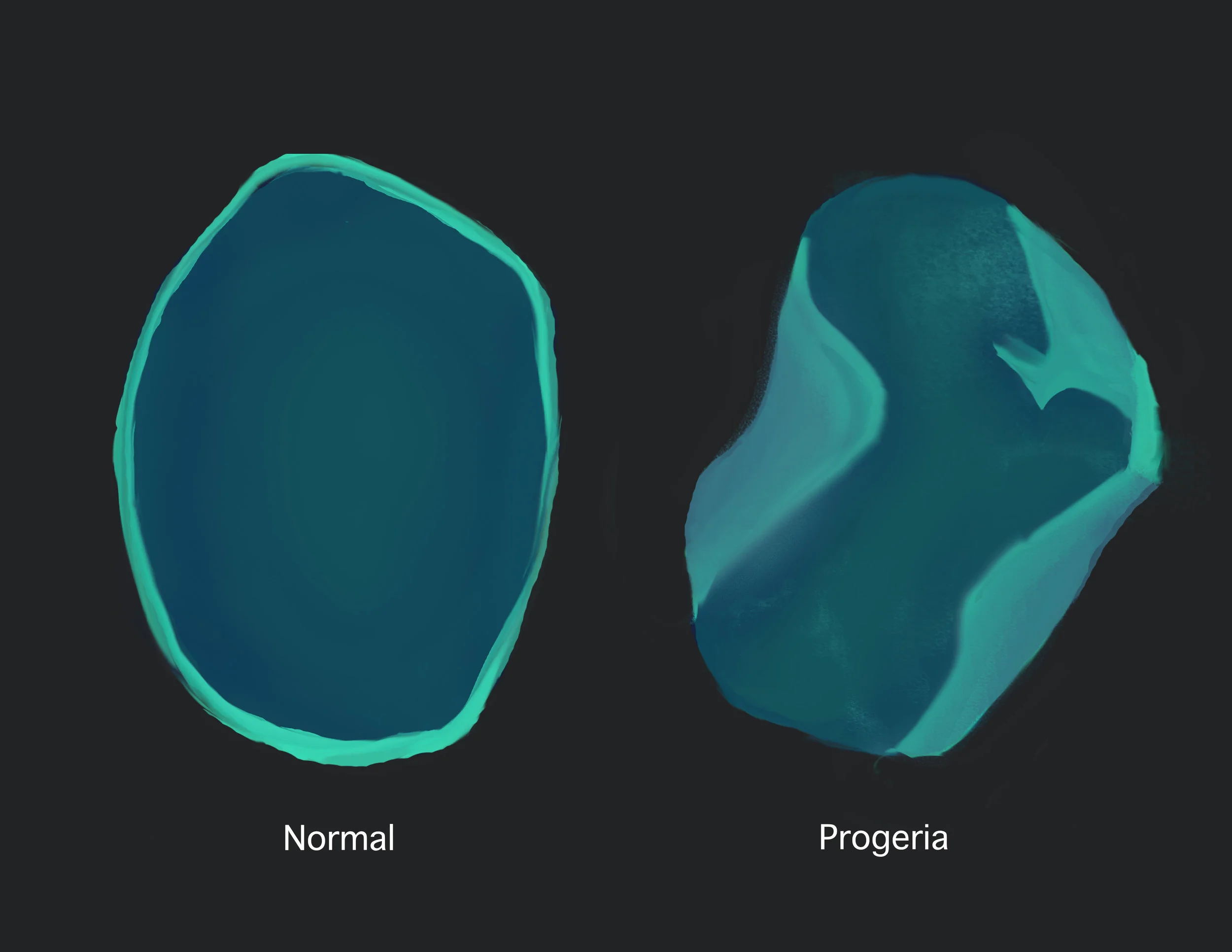

Appearance of a normal cell nucleus (left) and one from a patient with progeria (right).

Progeria is caused by a sporadic mutation in the LMNA gene coding for a structural protein called lamin A in the nuclei of body cells. A truncated version of lamin A called progerin is created that does not properly integrate, and disrupts the structure inside the nucleus, making it highly unstable.7,8 And this ultimately leads to premature aging of cells. Finally armed with this remarkable knowledge, the Diagnostics Testing Program was created in 2003 so that the children, their families and medical professionals could, for the first time, be given a definitive genetic diagnosis, and proper care and support from the community.6 To get to this point, all it took was inspiration from Sam’s positive outlook on life, and determination to not let any other child suffer from this uncertain disease. Researchers, including the world’s premier experts on progeria, are recently investigating potential ways of reducing the toxic progerin production and conducting in vivo trials on mouse models.10 Lonafarnib, an inhibitor of progerin production, is a potential treatment option as it reduces the symptoms commonly seen in the elderly.10 Over half the world’s identified population of children with progeria has travelled to Boston in 2015 to enrol in the clinical trial involving the effective Lonafarnib drug. And the researchers continue to study the common pathways between progeria and aging-related diseases.

Maintaining a positive outlook on life while battling the rarest, incurable disease of the world is not only a challenge, but also a dare that can sprout buds of inspiration, albeit small, in people’s hearts. The Progeria Research Foundation, the sole organization advocating for progeria, was created, and the historical gene discovery made with support garnered from Sam’s positive outlook on life and his parents’ determination. Now, children with progeria are given the care and attention that they should have received a century ago. Just as it takes a single point mutation to drastically change the life of a child, that single child alone can inspire an entire community to join the initiative to race against time in search for a cure. At the phenomenal rate the foundation has been progressing for the past 16 years, there is no doubt that a cure will be found.

After all, inspiration engenders movement.

Works Cited:

1. Botelho GC. Beloved teen Sam Berns dies at 17 after suffering from rare disease - CNN.com. CNN. 2015. Available at: http://www.cnn.com/2014/01/11/us/progeria-sam-berns-dies/.

2. Fine S, Fine A, Miriam W. Life According To Sam.; 2013. Available at: http://lifeaccordingtosam.com/#/trailer/.

3. Progeria Research Foundation. About progeria. ProgeriaResearch. Available at: http://www.progeriaresearch.org/about_progeria/.

4. Hutchinson J. Congenital Absence of Hair and Mammary Glands with Atrophic Condition of the Skin and its Appendages, in a Boy whose Mother had been almost wholly Bald from Alopecia Areata from the age of Six. Med Chir Trans.1886;69:473. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2121576/.

5. Progeria, A Form of Senilism. JAMA. 2004;292(12):1501. doi:10.1001/jama.292.12.1501.

6. Gordon A, Gordon L. The Progeria Research Foundation: its remarkable journey from obscurity to treatment. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs. 2014;2(11):1187-1195. doi:10.1517/21678707.2014.970172.

7. Sjakste N, Sjakste T. Nuclear matrix proteins and hereditary diseases. Russ J Genet. 2005;41(3):221-226. doi:10.1007/s11177-005-0076-y.

8. Cao K, Blair C, Faddah D et al. Progerin and telomere dysfunction collaborate to trigger cellular senescence in normal human fibroblasts. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(7):2833-2844. doi:10.1172/jci43578.

9. McClintock D, Ratner D, Lokuge M et al. The Mutant Form of Lamin A that Causes Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Is a Biomarker of Cellular Aging in Human Skin. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(12):e1269. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001269.

10. Gordon L, Kleinman M, Miller D et al. Clinical trial of a farnesyltransferase inhibitor in children with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome.Proc Natl AcadSci U S A. 2012;109(41):16666-16671. doi:10.1073/pnas.1202529109.

Cite This Article:

Sharma B., Zheng K., Chan G., Ho J. Progeria: Race Against Time. Illustrated by A. Mir. Rare Disease Review. July 2017. DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.10157.69601.